Well-Adjusted: Could Veterinary Spinal Manipulation Add Value to Your Show Calves’ Performance?

- Dallas Duncan

- Oct 28, 2025

- 4 min read

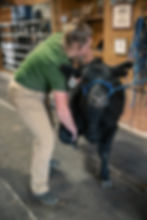

Part of keeping show cattle in tip-top shape includes making sure they’re moving fluidly, without pain or stiffness. Though medications to address this exist, some show barns are turning to a less conventional method of show calf maintenance — veterinary spinal manipulation, commonly referred to in human medicine as chiropractics.

That’s where Custom Livestock Solutions veterinarian Dr. Caitlin Quinn, DVM, comes in. After graduating from the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, she became certified in spinal manipulation at Chi University in Reddick, Florida.

The idea behind veterinary spinal manipulation is to increase the range of motion of a functional joint space.

“We think of joints as a very ball-and-socket or synovial-type joint,” Quinn says. “The reality is, there’s functional joints throughout the body — vertebrae, ribs, smaller bones — that interact with surrounding soft tissues.”

Any “restrictions” that interfere with a functional joint can lead to stiffness and impede range of motion, resulting in pain and/or negative nervous feedback.

For example, because of the way soft tissue pulls and keeps tension differently in the body, if an ankle hurts, the animal could overcompensate with its other leg. This may result in knee pain from too much strain.

Spinal manipulation involves motion palpation, where each individual joint surface or bony prominence is isolated and felt to ensure it moves appropriately. If it doesn’t, Quinn diagnoses a restriction, and then applies HVLA — high-velocity, low-amplitude — thrust, pressure that allows the restriction to adjust itself.

Veterinary spinal manipulation is most common with horses, though some veterinarians have dog and cat patients, too. Quinn may be one of the few to add cattle to the list of animals that experience benefits from the practice.

“The horse world can translate over and increase a show animal’s overall performance. Essentially, this is one of the minimally invasive, drug-free ways to do it; no withdrawals or anything they could be tested for at shows,” she says.

Her interest in veterinary spinal manipulation goes back several years to when she broke her collarbone in an equine accident. Quinn experienced a lot of secondary issues and wound up in a chiropractic clinic as a result. This gave her “perspective early on of how the body communicates as a whole.”

Quinn says veterinary spinal manipulation is more of a preventative or management technique: it won’t “fix” a disease, but it can help with managing the condition and its side effects, keeping the animal as loose and fluid as possible.

For cattle, in addition to addressing their range of motion, she says veterinary spinal manipulation can increase nervous signaling to muscles, allowing heifers and steers to fill out more evenly and appropriately.

“In order for a muscle to be healthy, it has to have good nervous stimulation or signaling,” Quinn says. “With bad restrictions, you can have muscle wasting or what appears to be muscle weakness.”

Like Quinn, Randi Leigh Davis of Block Show Cattle in Iva, South Carolina, grew up showing horses and was familiar with veterinary spinal manipulation as part of their maintenance.

“We’ve now been showing cows for a long time, and we used Dr. Amy [Goggans of CLS]. We were having some issues with a heifer being sound. She mentioned that Dr. Quinn could do the chiropractic work on the cows,” Davis says. “We’ve had a lot of success with it.”

One of their show heifers had a back right leg that wouldn’t stay sound, and there’s been a tremendous difference since Quinn began working on her, Davis said. Similar results were noted with shoulder conformation of another heifer — and now, the show calves all get veterinary spinal manipulation for preventative treatment.

“Starting calves with medical manipulation at a younger age allows them to adjust to the process and achieve better results,” Quinn says. “Older animals still benefit, but spinal manipulation isn’t a ‘quick fix’ and more benefit is achieved through repeated adjustments.”

In contrast to human chiropractors who are certified in that one skillset, those who practice on animals must first be veterinarians before they learn the specialty.

“If you’ve been trained in spinal manipulation, you have a beyond-vet training for the connections, the neuropathies, the tendons, what stabilizes the body, what destabilizes the body,” says Dr. Janine Weller, DVM, instructor at Chi University. “We don’t pop a bone around. We balance the entire animal.”

As with any medical procedure, there is the potential for risk. That’s another reason why spinal manipulation practitioners must be veterinarians: “They all leave [school] knowing if it doesn’t feel right, get an image. They’re going to get an image before they actually cowboy up and start moving stuff around in a bad way,” Weller says. “Dr. Quinn was trained very well to the point where she’s going to be more cautious; more careful.”

Animals that may not be the best-suited for veterinary spinal manipulation include those with acute neurological disease, trauma, a bone fracture that healed wrong, spinal fusions, and severe arthritis.

“We don’t have lay chiropractors in veterinary medicine,” Weller says. “Your veterinarian’s trained. They know what muscle’s going where … they know where your accessory nerves are coming off.”

Following an adjustment, animals can be sore for 24 to 48 hours. For that reason, Quinn does not recommend show calves undergo veterinary spinal manipulation too close to an event.

Davis says she “absolutely” thinks other show calf producers should consider adding the practice to their operations.

“It’s been a really good thing for us,” she says. “They’ve definitely been holding their own. They do really good for my son, so we’re happy with that.”